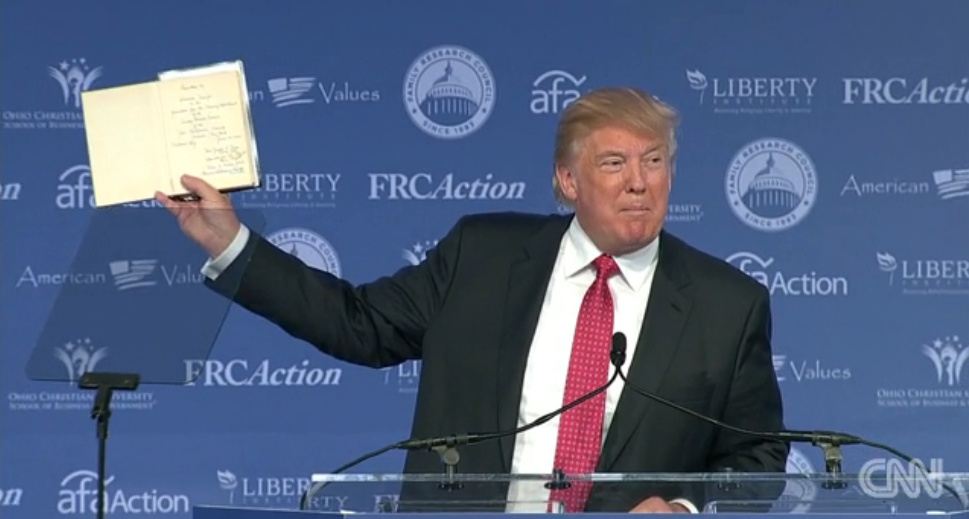

The evangelical divide over Trump has been widening for months, but it was only in recent weeks that the pro- and anti-Trump camps definitively split, with an increasing number of conservative evangelicals coming out forcefully against the candidate whom GOP consultant Rick Wilson once called “Cheeto Jesus.” The breaking point came on June 21, when Trump—ironically in an effort to appease the religious right—met with nearly a thousand evangelical leaders and announced a 25-person “evangelical advisory board” to help him reach conservative Christian voters.

Almost all the members of that board have histories of being right-leaning, pro-life and pro-Israel—typical for conservative Christians. But as Ruth Graham noted at Slate, the group is really a who’s-who of former evangelical leaders: Ralph Reed, former leader of the Christian Coalition; Ronnie Floyd, former president of the Southern Baptist Convention; and James Dobson, former president of Focus on the Family. It probably doesn’t come as a surprise that the board is mostly older (average age: 64), mostly male and mostly white, with only four people of color. They are a remnant, in other words, of the old guard Moral Majority-era conservative evangelicals whose political influence, on issues like same-sex marriage, contraception and school prayer, was already waning.

After all, Evangelicalism today looks very different from the bygone era of the Dobsons and the Falwells. (Jerry Falwell, Jr., the son of the Moral Majority’s founder, is also on Trump’s board.) For years, evangelicals have been leading the charge against climate change and supporting immigration reform, and 27 percent of white evangelicals now support same-sex marriage, up from 13 percent in 2001. Demographically, the fastest-growing segment of evangelicals in America is Latinos.

Christian blogger Fred Clark called the advisory board a “B-list of second-tier religious right figures along with a handful of peaked-long-ago relics.” The Hispanic Baptist Pastors Alliance took offense too, in a statement warning that “joining this board is not the wisest way to be salt and light” and cautioning against “jumping into a crowded office where the weed and wheat are undistinguishable.” It was essentially a call to stay out of politics—a rejection of the basic premise of the Moral Majority, that Christians ought to influence politics to see God’s Kingdom come.

Trump’s board was criticized for much more than its demographic makeup, though. Russell Moore—an influential leader in the Southern Baptist Convention with a history of theologically and politically conservative views—immediately denounced the board’s “heretical prosperity gospel hucksters hailed as spiritual leaders.” Presumably he was taking aim at people like televangelists Kenneth and Gloria Copeland and Paula White, who are known for preaching the “prosperity gospel”; the Senate investigated the spending habits of their two ministries in 2007, though neither was found to have committed any wrongdoing. Still, White—who has been a spiritual adviser to Trump for years—is viewed skeptically by most evangelicals.

For some on the religious right, Trump’s alignment of himself with the movement’s old guard and its “prosperity gospel” wing fundamentally calls into question what the group’s role in politics should be.