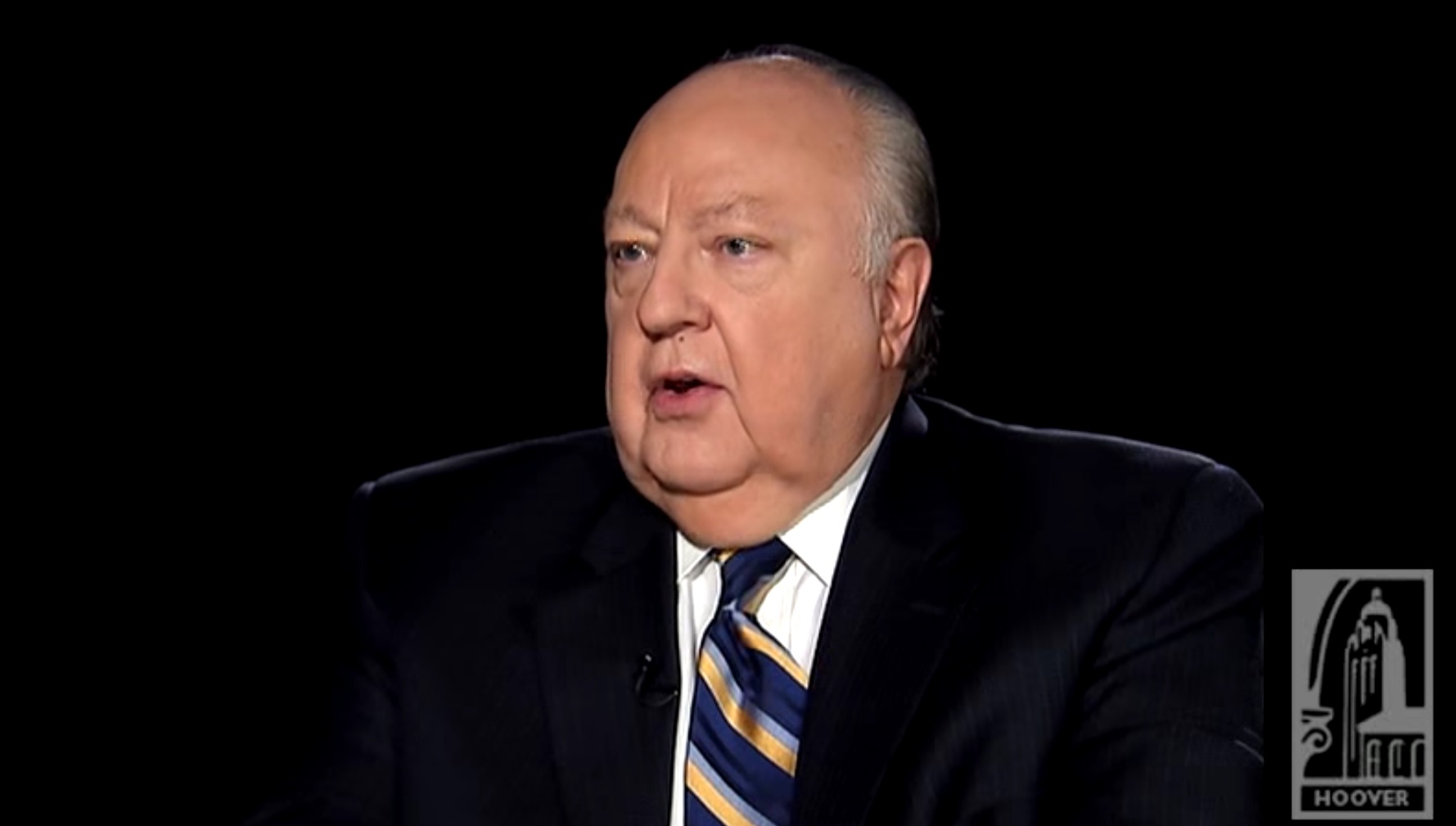

It took 15 days to end the mighty 20-year reign of Roger Ailes at Fox News, one of the most storied runs in media and political history. Ailes built not just a conservative cable news channel but something like a fourth branch of government; a propaganda arm for the GOP; an organization that determined Republican presidential candidates, sold wars, and decided the issues of the day for 2 million viewers. That the place turned out to be rife with grotesque abuses of power has left even its liberal critics stunned. More than two dozen women have come forward to accuse Ailes of sexual harassment, and what they have exposed is both a culture of misogyny and one of corruption and surveillance, smear campaigns and hush money, with implications reaching far wider than one disturbed man at the top.

It began, of course, with a lawsuit. Of all the people who might have brought down Ailes, the former Fox & Friends anchor Gretchen Carlsonwas among the least likely. A 50-year-old former Miss America, she was the archetypal Fox anchor: blonde, right-wing, proudly anti-intellectual. A memorable Daily Show clip showed Carlson saying she needed to Google the words czar and ignoramus. But television is a deceptive medium. Off-camera, Carlson is a Stanford- and Oxford-educated feminist who chafed at the culture of Fox News. When Ailes made harassing comments to her about her legs and suggested she wear tight-fitting outfits after she joined the network in 2005, she tried to ignore him. But eventually he pushed her too far. When Carlson complained to her supervisor in 2009 about her co-host Steve Doocy, who she said condescended to her on and off the air, Ailes responded that she was “a man hater” and a “killer” who “needed to get along with the boys.” After this conversation, Carlson says, her role on the show diminished. In September 2013, Ailes demoted her from the morning show Fox & Friends to the lower-rated 2 p.m. time slot.

Carlson knew her situation was far from unique: It was common knowledge at Fox that Ailes frequently made inappropriate comments to women in private meetings and asked them to twirl around so he could examine their figures; and there were persistent rumors that Ailes propositioned female employees for sexual favors. The culture of fear at Fox was such that no one would dare come forward. Ailes was notoriously paranoid and secretive — he built a multiroom security bunker under his home and kept a gun in his Fox office, according to Vanity Fair — and he demanded absolute loyalty from those who worked for him. He was known for monitoring employee emails and phone conversations and hiring private investigators. “Watch out for the enemy within,” he told Fox’s staff during one companywide meeting.

Taking on Ailes was dangerous, but Carlson was determined to fight back. She settled on a simple strategy: She would turn the tables on his surveillance. Beginning in 2014, according to a person familiar with the lawsuit, Carlson brought her iPhone to meetings in Ailes’s office and secretly recorded him saying the kinds of things he’d been saying to her all along. “I think you and I should have had a sexual relationship a long time ago, and then you’d be good and better and I’d be good and better. Sometimes problems are easier to solve” that way, he said in one conversation. “I’m sure you can do sweet nothings when you want to,” he said another time. […]

Carlson and Smith were well aware that suing Ailes for sexual harassment would be big news in a post-Cosby media culture that had become more sensitive to women claiming harassment; still, they were anxious about going up against such a powerful adversary. What they couldn’t have known was that Ailes’s position at Fox was already much more precarious than ever before.

When Carlson filed her suit, 21st Century Fox executive chairman Rupert Murdoch and his sons, James and Lachlan, were in Sun Valley, Idaho, attending the annual Allen & Company media conference. James and Lachlan, who were not fans of Ailes’s, had been taking on bigger and bigger roles in the company in recent years (technically, and much to his irritation, Ailes has reported to them since June 2015), and they were quick to recognize the suit as both a big problem — and an opportunity. Within hours, the Murdoch heirs persuaded their 85-year-old father, who historically has been loath to undercut Ailes publicly, to release a statement saying, “We take these matters seriously.” They also persuaded Rupert to hire the law firm Paul, Weiss, Rifkind, Wharton & Garrison to conduct aninternal investigation into the matter. Making things look worse for Ailes, three days after Carlson’s suit was filed, New York published the accounts of six other women who claimed to have been harassed by Ailes over the course of three decades.

A few hours after the New York report, Ailes held an emergency meeting with longtime friend Rudy Giuliani and lawyer Marc Mukasey at his home in Garrison, New York, according to a high-level Fox source. Ailes vehemently denied the allegations. The next morning, Ailes and his wife, Elizabeth, turned his second-floor office at Fox News into a war room. “It’s all bullshit! We have to get in front of this,” he said to executives. “This is not about money. This is about his legacy,” said Elizabeth, according to a Fox source. As part of his counteroffensive, Ailes rallied Fox News employees to defend him in the press. Fox & Friends host Ainsley Earhardt called Ailes a “family man”; Fox Business anchor Neil Cavuto wrote, reportedly of his own volition, an op-ed labeling Ailes’s accusers “sick.” Ailes’s legal team attempted to intimidate a former Fox correspondent named Rudi Bakhtiar who spoke to New York about her harassment.

Ailes told executives that he was being persecuted by the liberal media and by the Murdoch sons. According to a high-level source inside the company, Ailes complained to 21st Century Fox general counsel Gerson Zweifach that James, whose wife had worked for the Clinton Foundation, was trying to get rid of him in order to help elect Hillary Clinton. At one point, Ailes threatened to fly to France, where Rupert was vacationing with his wife, Jerry Hall, in an effort to save his job. Perhaps Murdoch told him not to bother, because the trip never happened.

According to a person close to the Murdochs, Rupert’s first instinct was to protect Ailes, who had worked for him for two decades. The elder Murdoch can be extremely loyal to executives who run his companies, even when they cross the line. (The most famous example of this is Sun editor Rebekah Brooks, whom he kept in the fold after the U.K. phone-hacking scandal.) Also, Ailes has made the Murdochs a lot of money — Fox News generates more than $1 billion annually, which accounts for 20 percent of 21st Century Fox’s profits — and Rupert worried that perhaps only Ailes could run the network so successfully. “Rupert is in the clouds; he didn’t appreciate how toxic an environment it was that Ailes created,” a person close to the Murdochs said. “If the money hadn’t been so good, then maybe they would have asked questions.”

Beyond the James and Lachlan factor, the relationship between Murdoch and Ailes was becoming strained: Murdoch didn’t like that Ailes was putting Fox so squarely behind the candidacy of Donald Trump. And he had begun to worry less about whether Fox could endure without its creator. (In recent years, Ailes had taken extended health leaves from Fox and the ratings held.) Now Ailes had made himself a true liability: More than two dozen Fox News women told the Paul, Weiss lawyers about their harassment in graphic terms. The most significant of the accusers wasMegyn Kelly, who is in contract negotiations with Fox and is considered by the Murdochs to be the future of the network. So important to Fox is Kelly that Lachlan personally approved her reported $6 million book advance from Murdoch-controlled publisher HarperCollins, according to two sources.