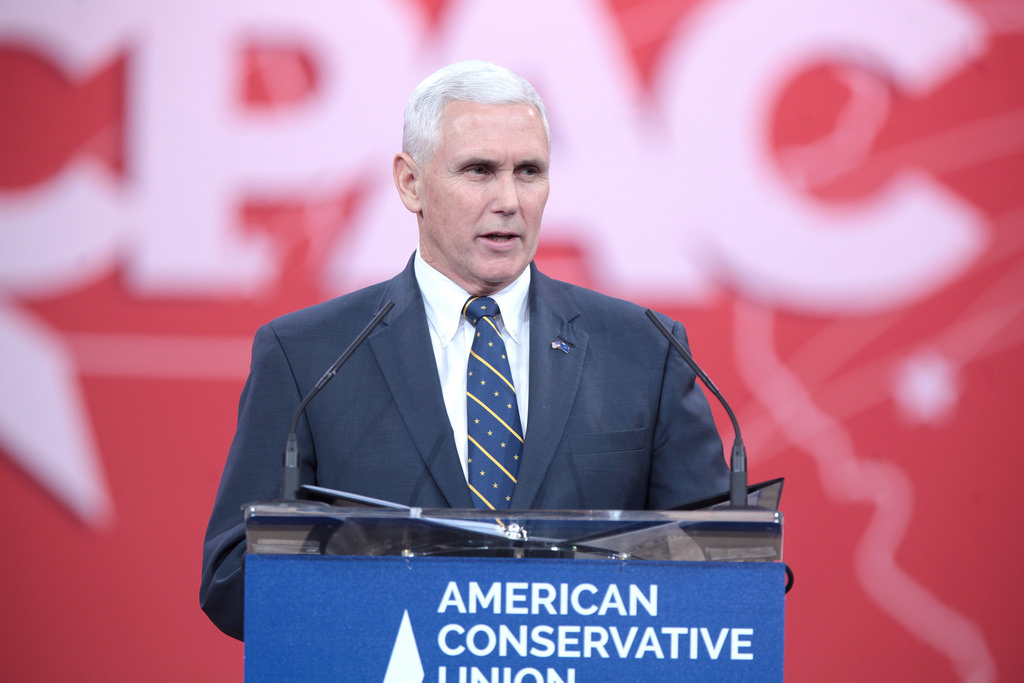

Since 2000, only one vice-presidential candidate (John Edwards in 2004) was from a state that could have been competitive in November. Pence, the incumbent governor of Indiana, doesn’t break that pattern: Recent polls have Trump comfortably ahead in his state. […]

However, in a new study published in American Politics Research, we come to a different conclusion. We find that the average vice-presidential home-state advantage is considerably higher: nearly 3 percentage points, on average.

We also find that this advantage exists in battleground states with enough electoral votes to matter. This means that a vice-presidential candidate from an important swing state could very well make the difference between winning or losing.

Why do our results differ so much from the traditional findings?

Typically, people measure the home-state advantage by taking account of both the national vote in that year’s presidential election and the average presidential election performance of the party over several previous elections. The logic is to estimate how well the party did in the vice-presidential nominee’s home state relative to how it should do. The difference between the actual vote and the expected vote is the home-state advantage.

This strategy has several problems, however. One is that running mates tend to be selected from states in which the party has seen a decline in popularity in the run-up to the election year. As a result, averaging the party’s performance over previous elections generally overestimates the strength of the party there, and thus underestimates the VP candidate’s home-state advantage.