If one wants to understand the rise of Donald Trump, it’s useful to consider two narratives.

The first narrative goes like this: The fortunes of the white working class have been waning for decades. Real median wages for people without a college degree are lower today than they were forty years ago. Income inequality is now back to where it was during the Gilded Age. Meanwhile, trust and social cohesion have plummeted. As each new technological advance leaves low-skilled workers out in the cold and the ceaseless march of globalization destroys both jobs and decent wages, once-vibrant regions have been hollowed out and entire communities ruined. For a generation raised to believe in American exceptionalism, this seemed like a betrayal, both personal and national. But nobody seemed to care. Republicans offered tired old trickle-down economics, insisting that the American dream was just around the corner. All we had to do was give tax cuts to the “job creators,” deregulate large swaths of the economy, and remove the soft mattress of social protection to give people the motivation to work hard. For their part, Democrats turned away from the people who once constituted their core constituency, entranced by the geniuses of the “creative classes” in Silicon Valley and Wall Street and devoted to the narrow politics of personal identity. Nobody spoke for the working class anymore. Then along came someone who not only spoke the language of class but mastered its nuances: Donald Trump.

The second narrative goes like this: Race has always been the dark underbelly of American politics. Thanks to the Civil Rights Act and Richard Nixon’s strategy of stoking racial resentment, white voters in the South deserted the liberal Democratic Party for a GOP that rebranded itself increasingly as a party of white interests and white identity. Nixon’s “Southern Strategy” took a while to ripen and rarely declared itself explicitly. It often took the form of racist “dog whistles”—think of Ronald Reagan railing against “welfare queens,” and Jesse Helms running campaign ads implying that minorities were cheating white people out of jobs. A sense of insecurity grew. White Americans saw clearly that their dominance—economic, political, and cultural—was fading. The politics of race-tinged resentment grew worse over time, reaching fever pitch with the election of Barack Obama and the rise of the Tea Party, which ominously promised to “take back the country.” All of this laid the groundwork for Donald Trump, who mastered the language of white resentment and tapped into the growing rage against cultural elites.

So which of these two narratives is the true one? Both, actually.

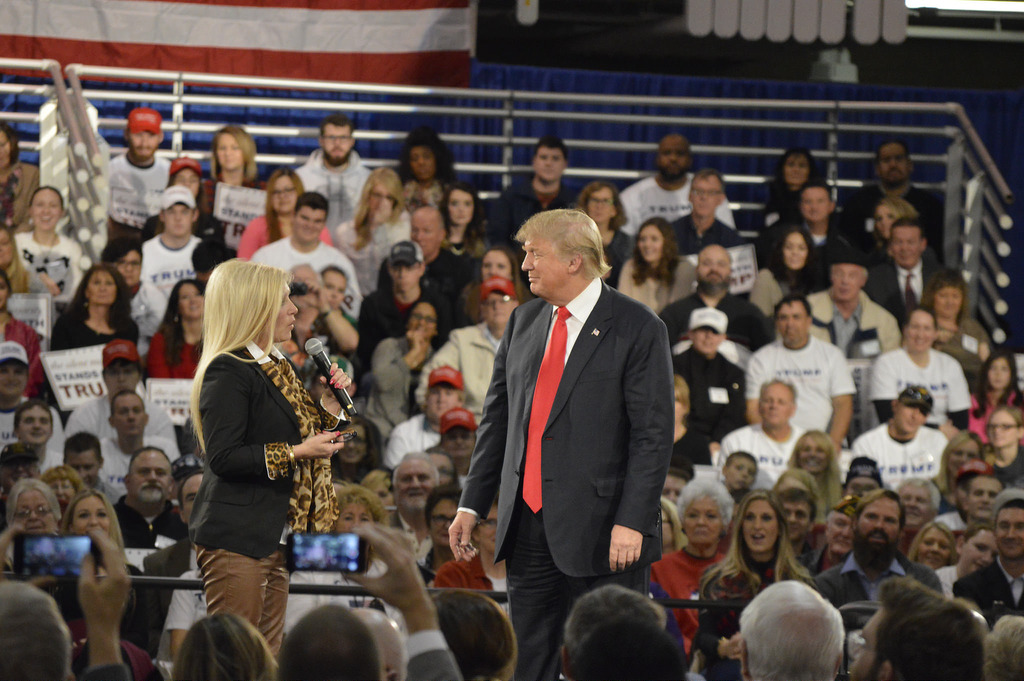

Photo by aj.hanson1