If 2012 was the presidential election in which data-driven journalism really came into its own, the 2016 Republican nomination contest has been the one in which the conventional wisdom has continually been shattered.

Besides driving Republican officials to distraction, Donald Trump has been the bane of journalists from data geeks like Nate Silver and the New York Times’s Nate Cohn to more old school analysts like Ron Brownstein of National Journal. The former television star’s unorthodox background and brash demeanor has upended the conventional wisdom about how American political parties’ nominations are determined.

It wasn’t supposed to work this way. For many months after he announced his candidacy, most political observers figured Trump didn’t have a prayer.

In an August 2015 post about a month after Trump declared, Silver gave him a mere 2 percent chance of securing the GOP nomination. Operatives within the Jeb Bush campaign literally greeted the titian tycoon’s official announcement with “barely concealed delight” according to the New York Times.

It’s the beginning of March and there are still many delegates Trump needs in order to reach 1,237—the number needed to receive the nomination at the Republican National Convention on the first ballot—but the odds are obviously in Trump’s favor now.

With a few notable exceptions such as Scott Adams, Rush Limbaugh, and Pat Buchanan, most political observers figured Trump would share the fate of previous conservative insurgent candidates like Michele Bachmann, Herman Cain, or Rick Santorum who all became overnight favorites but then saw their popularity wither as they received more attention from the media and rival campaigns. The general assumption was that even though he began leading the pack in mid-July of 2015, Trump would eventually fall back and be overtaken by a more conventional candidate.

There was good reason to suspect this. After all, it was a pattern other candidates had followed, one called “discovery” and “scrutiny” by political scientists John Sides and Lynn Vavreck in their excellent book The Gamble: Choice and Chance in the 2012 Presidential Election.

But Donald Trump broke the model. While he has continuously received a massively greater amount of media coverage than the other candidates, the additional publicity has not harmed Trump’s numbers. In fact, they’ve only increased since he began. Defying numerous predictions that Trump had a low “ceiling” of support, a majority of Republicans in surveys said they were willing to vote for him as early as December. As of January, 56 percent of Republican-leaning voters said they thought he would be a good or great president.

As 2015 wore on, some observers (like Bloomberg Politics reporter Sahil Kapur) argued that the dynamics of the race—such as the highly divided field and his strong appeal across states and ideological groups—actually favored a Trump victory. Generally speaking, these predictions had no effect on the opinions of the biggest donors and the highest-level consultants. (I’m pretty confident that none of them was persuaded by an essay I published in November saying Trump had the edge.)

But it wasn’t just political writers that the right’s grandest of poohbahs ignored. They also wouldn’t listen to the opinions of experienced GOP operatives like Alex Castellanos, Rick Wilson, and Liz Mair, all of whom warned that Trump could actually prevail.

In October, Stuart Stevens, Mitt Romney’s chief political strategist, insisted Trump would drop out before the Iowa caucuses. He was only slightly less confident in December when he argued that Trump would not win a single state. Karl “The Architect” Rove wasn’t as biting in his predictions but he was certainly in agreement with Stevens. At the end of November, the former George W. Bush strategist said that only Jeb Bush, Chris Christie, and Marco Rubio had good chances of becoming the Republican nominee.

Unlike the magical thinking and data-denying that Republican election consultants pushed in 2012 that culminated in Rove’s embarrassing refusal to admit defeat on live television, the insouciance about Trump was actually based on some valid ideas. Nor were the consultants alone in continuing to say Trump didn’t have a prayer. In December, Nate Cohn of the New York Times correctly noted several examples from past cycles in which the candidate who was the front-runner at year’s end failed to become the nominee, and accordingly pronounced Trump’s chances as “not good.” Silver also continued to deny that the real estate magnate could pull it off.

If you were looking to, there were other reasons to downgrade Trump’s prospects. He spent basically nothing on television advertising and he hired far fewer people in Iowa and New Hampshire compared to his rivals. Additionally, until February 24, despite having led the GOP pack for months on end, Trump hadn’t received a single endorsement from a currently serving Republican elected official. The front-runner’s inability to muster testimonials was a big deal to political scientists and journalists who have touted the idea of an “Invisible Primary” where various candidates jockey for position outside of public view to get the best staff members and the most money.

There certainly is data behind that supposition, even though the number of open nomination contests in history is still rather small. Nonetheless, the notion that party grandees were the main determiners of their own standard-bearers caught on among journalists like wildfire. The title of a 2008 book, The Party Decides, became a mantra that was almost inescapable up until Donald Trump’s victories in New Hampshire, South Carolina, and Nevada. Many political observers simply couldn’t believe it was possible that Trump would be allowed to get to the point where he is today, on the cusp of victory.

The question of why the Republican powers-that-be didn’t spring into action until Trump had notched victories in three separate elections is one that journalists and historians will be asking for many years. The answer may already have been provided, however, by Daniel Drezner, a professor of international politics at Tufts University who also frequently comments on electoral matters.

Drezner offers two reasons why no one decided to act. The first is that it attacking Trump was not in the interest of any of his rivals individually. Not too long after he entered the race, it became clear that Trump was very adept at using his speaking and adversarial negotiation skills in the political arena as he demolished the poll numbers of Jeb Bush, Rick Perry, Rand Paul, and Ben Carson. Beyond that, many of the campaigns and their supporters remained convinced that Trump would finally say something so outrageous that his candidacy would implode and therefore they had best play nice so that they could inherit Trump’s voters.

This created a social dilemma in which all of the non-Trump candidates wanted the same outcome but were unwilling to cooperate in order to attain it. Instead of banding together to vanquish the outsider as Ted Cruz and Marco Rubio did in the most recent debate, the other 16 candidates mostly did nothing until their funds or support dwindled away. Once that happened, in succession, each failing candidate would launch a kamikaze attack on Trump that inevitably failed.

Even now as Trump is within sight of victory, both Cruz and Rubio are continuing their protracted grudge match over who will become the designated anti-Trump.

Drezner’s other theory is that the fact that so many people believed Trump would be prevented from becoming the nominee—whether by the voters suddenly, magically becoming more “serious” or right-leaning fat cats deciding to spend tens of millions on attack ads against him—made it become a self-defeating prophecy. The candidates, donors, and their consultant remoras never bothered to take action because each of them figured that someone else would do it. Everyone figured out that the party would decide, somehow, that it would get rid of the interloper.

At first blush, Drezner’s hypotheses would seem to mean that the problem with The Party Decides is that it was too true to be true.

But that isn’t actually what the book or the theory says. As Silver noted in a post he wrote at the end of January after re-reading the book, the authors’ argument rests upon a rather different definition of “the party” or “The Establishment.”

While conservative activists, commentators, and journalists seem to think of the establishment as official Republican Party functionaries, the authors of the now-maligned theory have a much more sophisticated and inclusive definition which also includes the very same talk show hosts, television commentators, and writers who erroneously believe themselves to be outsiders looking in.

This definition is also surely the one that Trump supporters have in mind when they think of Fox News journalists like Megyn Kelly, the participants at the recently concluded CPAC, the numerous highly paid heads of various activist and policy organizations, and the stalwart Republicans constantly talking about #NeverTrump on Twitter.

When the question of right-wing consensus is looked at in this light, it becomes obvious why Donald Trump has done so well. The party has decided that it doesn’t like Trump, but it is incapable of deciding how to rid itself of him. Ask two Republicans and you’ll get four separate opinions as to how to stop the abomination of desolation of a Trump nomination.

Aside from dealing with Trump, however, the right’s inability to decide is evident in the numerous difficulties John Boehner faced in his tenure as Speaker of the House trying to pass basic legislation and the astonishing willingness of many conservative lawmakers to repeatedly risk credit default by refusing to raise the debt ceiling. Conservative commentators and activist organizations also are greatly divided in their ideas for governance, with many thinking that even the slightest compromise is an abject defeat and humiliation. Then there’s foreign policy where it seems that both the analysts and politicians appear to have learned almost nothing from the disasters of the Bush years as they proclaim their desire to militarily intervene in Syria, Ukraine, and many other places.

But even if we limit our definition of the party to just Republican politicians, the inability of the establishment to decide is also evident. As mentioned above, Donald Trump had zero endorsements from currently serving elected officials until February 24. But even the other candidates have had difficulty getting endorsements this cycle.

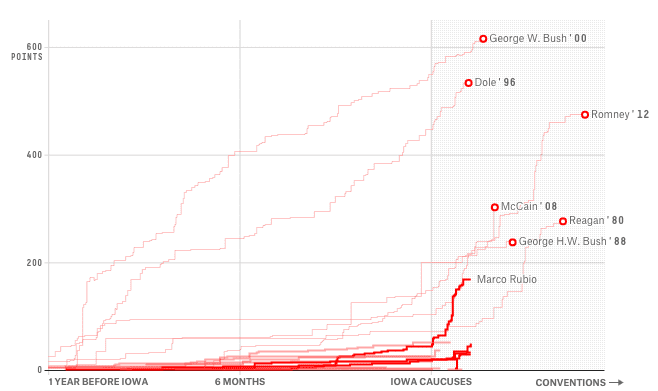

As Silver and his colleagues have documented via their “Endorsement Primary” tool, Republican officeholders are generally not endorsing. The chart below is even more damning for the GOP, however, because it uses the most popular endorsement recipient, Marco Rubio, who is now a distant third in the actual race. Were Trump to be on the chart, he would only have 29 points (follow the link for how they’re calculated), far lower than any other previous candidate in recent Republican history.

There is one other notable aspect to the chart above. The second-lowest scoring candidate 30 days after the Iowa caucuses is Ronald Reagan during his 1980 run.

Perhaps party official seals of approval are not as significant as they’re made out to be, but if there is something to them, it would seem to indicate that the turmoil currently roiling the right is indicative of big changes. It’s not remembered much now but the Reagan nomination was actually rather controversial in its day with a many self-described liberal Republicans following Congressman John Anderson out of the party to support his independent candidacy.

A Donald Trump nomination will either see a dramatic expansion of the Republican voting rolls with a partial exit of a disgruntled minority or it will see the opposite: a mass exodus from the GOP and the consignment of those who remain to the ash heap of history. Trump will either be the next Reagan or he will be an anti-Reagan.

The very fact that the latter scenario is even possible means that the party—the politicians, the donors, their advisors, the activist leaders, the policy mavens—has failed. A functioning and healthy party would have avoided the situation in the first place by creating new policies that better serve the public and Republican voters. That the party then declined to do anything against him when it could have suggests that regardless of whether Trump actually gets the GOP nomination, the American right is in need of wholesale reform at the very highest echelons. That’s because Donald Trump is not the cause of the right’s problems; he is the consequence of the right’s problems.