On Thursday, 13 of the 14 GOP candidates for president stopped by the Republican Jewish Coalition’s annual meeting, each boasting of how he or she was the best choice for adherents of the oldest Abrahamic religion. As would be expected, awkward pandering was a top priority on the agenda.

“Last night, I was watching ‘Schindler’s List,’” announced former Virginia governor Jim Gilmore. It was the highest compliment a politician could give, almost a direct reference to a 2013 Pew Research poll which indicated that 73 percent of Jewish Americans believe that remembering the Holocaust is an essential part of their ethnic identity.

Retired surgeon Ben Carson read his speech almost entirely from notes as he delivered what amounted to little more than a collection of trivia facts about Israel interspersed with mispronunciations of the name of the Palestinian terrorist group, Hamas. He also lent credence to a discredited theory about the back of the $1 bill allegedly featuring a Star of David that recalled his incorrect hypothesis about the origins of the Egyptian pyramids.

Former Pennsylvania senator Rick Santorum spoke of his experiences working with Joe Lieberman, perhaps the most well-known Jewish politician in the country. Businessman Donald Trump jokingly boasted of his love for negotiations and how this was something he shared with “99.9 percent” of attendees.

Many candidates also made a point to emphasize their support for Israel. Texas senator Ted Cruz said it was reason enough for Jews who disagreed with him on abortion or gay rights to fill in a ballot for him.

Republican Frustration

Despite the existence of groups like the Republican Jewish Coalition and many outreach efforts, the GOP at large has had a tough time convincing Jewish Americans to get on board. Since the 1980s, the group has consistently given Democrats about 75 percent of their votes.

It’s long been a source of befuddlement for many Republicans, particularly because their party has made supporting a bellicose Middle East policy one of its top priorities, something they’ve believed would be desirable. In most surveys, however, Jewish-Americans have tended to support President Obama’s policies, including his frequently critical responses to Israeli prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu.

Michele Bachmann, a former Republican House member and presidential candidate, expressed this frustration in a rather extraordinary fashion in a 2014 interview with a Christian radio program. In the segment, she accused American Jews of having “sold out Israel” by voting to re-elect President Barack Obama despite his willingness to negotiate an end to trade sanctions against Iran:

“The Jewish community gave him their votes, their support, their financial support and as recently as last week, forty-eight Jewish donors who are big contributors to the president wrote a letter to the Democrat senators in the U.S. Senate to tell them to not advance sanctions against Iran,” she said.

“What has been shocking has been seeing and observing Jewish organizations who, it appears, have made it their priority to support the political priority and the political ambitions of the president over the best interests of Israel. They sold out Israel.”

While the former representative is clearly an outlier in her anger against Jewish people for supporting President Obama’s policies–especially since she believes they will unwittingly bring about the end of the world and the return of Jesus–she is not alone in having her hopes dashed that someday, American Jews will vote for Democrats.

This past March, Steve King (R-Iowa) expressed the frustration of many GOPers in an interview with the Boston Herald that “I don’t understand how Jews in America can be Democrats first and Jewish second and support Israel along the line of just following their president.”

It isn’t just Republicans who have been straining to find any sort of sign that Jews are turning Republican, however. Even before sociologist Milton Himmelfarb quipped in 1973 that that “Jews earn like Episcopalians and vote like Puerto Ricans,” many top publications have been writing this story for many years as historian Josh Zeitz noted:

As has been the case almost every four years since the early 1970s, and much like Charlie Brown to Lucy’s football, the political media is waiting expectantly for an electoral swing. “Cracks Appear in Democratic-Jewish Alliance Over Iran Deal, Netanyahu,” the Wall Street Journal announced over the weekend. “G.O.P.’s Israel Support Deepens as Political Contributions Shift,” the New York Times added.

The problem is that we’ve been reading this headline for the better part of half a century. “The Jewish Vote” (1972). “Anti-Semitism Issue Worries Party” (1984). “Bush and Dukakis Are Engaging in Early Battle Over the Jewish Vote” (1988). “G.O.P. Courts Jews With Eye to Future” (1992). “Kemp Lines Up Solidly Behind Netanyahu” (1996). “Republicans Go After Jewish Vote” (2012).

The American Jewish Difference

The strong Democratic loyalty of American Jews sets them apart from Jewish people worldwide, most of whom tend to reside on the center-right side of the political spectrum.

Among the few American conservatives who have noted this fact has been Daniel Greenfield in a May essay for FrontPage which noted that:

In the last UK election, 70% of British Jews polled as voting conservative. Only 22 percent backed Labour. It didn’t help that Labour’s Ed Miliband was ethnically Jewish because he was anti-Israel. Even the former director of Labour Friends of Israel announced that she was voting for Cameron. […]

In the 2011 election, Canada’s Conservatives picked up 52 percent of the Jewish vote. The Jewish vote lagged behind the Protestant vote by only 3 percent. Experts cited the key element as being Prime Minister Harper’s support for Israel. That and growing concern among Canadian Jews about Islam.

British, Canadian and Israeli Jews stand on one side. It’s American liberal Jews that are isolated.

In Australia’s last election, it was reported that there was a near consensus among Jewish community leaders in favor of the more conservative Liberal Party over Labor. A majority of Sydney’s most Jewish electorates are held by Liberal party candidates.

Why are American Jews so different from their peers in other countries? Greenfield and others have offered various explanations: antisemitism on the political left is stronger outside of the United States, Jews’ heritage of being a historically persecuted minority group makes them identify with left-wing politics, or that the Bible’s stories of slavery and escape make Judaism a religion inherently interested in combating economic inequality.

The trouble with all of these theories is that they miss a lot of the facts. For the most part, theologically conservative Protestants only recently became philosemitic after the creation of Israel in the middle of the 20th century. And if being persecuted descendants of slaves amounted to any effect on political identity, it makes no sense that American Jews would somehow be different from their counterparts in other nations who share the exact same literature and history.

An Exceptional Liberty: Religious Freedom

If those explanations are unpersuasive, what explains Jewish Americans’ anomalous leftward lean?

In short: American exceptionalism, a term conservatives love talking about in the context of the country’s founding on the basis that all people are entitled basic rights that no government can justly deny, a concept that was unheard of in 1776.

One significant component of those freedoms which does not get a lot of discussion from the right today is the idea of separation of church and state, another brand-new legal concept during America’s founding.

According to University of Florida political science professor Kenneth Wald, the concept of separation of church and state is crucial to understanding the American Jewish political identity:

Only in the new United States, at least at the federal level, was political equality something Jews held “as of right together with all other citizens.” Whereas Jews on the Continent might be tolerated or protected, Hannah Adams wrote (1817, 132), the United States had gone further by vesting them with “all the rights of citizens.”

The contrast with the European heritage could not have been starker. […] Jews, the eternal alienated people who rejected the Christian God, could not be a permanent fixture in such a society. Hence, the limited tolerance granted them in earlier periods grew increasingly anachronistic and subject to revocation. By the mid-16th century, Europe was largely devoid of professing Jews. Even when they returned to the continent in the 18th and 19th centuries, Jews were still not considered equal. [citations omitted]

Wald’s paper contains numerous quotations from colonial Jewish figures extolling the Constitution and and its guarantee against religious requirements for federal officeholders. Prizing the unique gift they had been given by James Madison and the other Founding Fathers, Wald’s paper documents how American Jews devoted themselves to preserving the fourth president’s “favorite principle” of “perfect separation between ecclesiastical and civil matters” by protesting strongly against discrimination attempts.

In an interview with the Washington Post’s Monkey Cage political science blog, Wald elaborated on how the importance of religious neutrality for American Jews has made their voting behavior completely decoupled from economics.

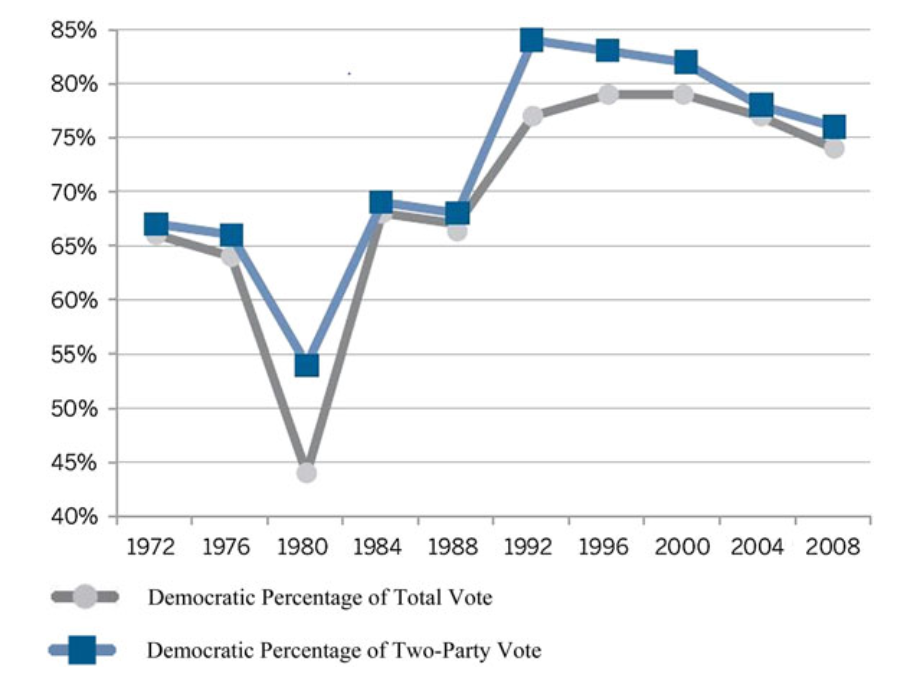

Most Jews embrace the classic liberal regime of religion and state in the U.S. and typically support candidates that they perceive as most committed to it. Since the New Deal at least, the Democrats have been that party, but the pattern has occasionally been disrupted. For example, under the influence of identity politics in the late 1960s, Democrats favored policies that seemed to some American Jews to violate the classic liberal idea by granting legal privileges and benefits on the basis of race and gender. In reaction, the Democratic vote share among Jews dropped significantly and oscillated in the 1970s and 1980s.

When, however, the Republican party reached out to white Protestant evangelicals, who eventually came to constitute the party’s base, Jews reacted negatively because they perceived a threat to the liberal regime. Evangelicals, with their “God talk,” insistence on a “Christian America,” and general willingness to deny fundamental liberties to some minorities on religious grounds, struck many American Jews as a fundamental danger to core values of the polity. Accordingly, Jewish support for Democratic presidential nominees rose from roughly two-thirds to three-fourths in the 1990s and thereafter.

Source: Mark S. Mellman, Aaron Strauss, Kenneth D. Wald.”Jewish American Voting Behavior 1972-2008: Just the Facts.”

Even the glaring exception, the Republican-oriented Orthodox Jewish community, manifests similar dynamics. Less concerned with integrating in the manner of most American Jews, some of the Orthodox support Republican candidates who promise policies like tuition tax credits that might facilitate communal integrity. The point is that Jews strategically adapt their political behavior in response to the agendas and rhetoric of the political parties.

Lindsey Graham’s Challenge to the GOP

Most Republican campaign consultants and politicians appear not to have realized this fact yet. One candidate who does appear to understand is South Carolina senator Lindsey Graham whose impromptu speech to the RJC gathering on Thursday focused very little on Jewish-related issues and more on the American experience and why Republicans ought to preserve it for people who are not just white Christians.

Despite polling about only 1 percent in national polls, Graham was regarded as the best speaker of the event by attendees. He even managed to trend on Twitter, likely the first time ever for him. Watch the speech below starting at about the 28:30 mark and you’ll see why:

How many of you believe that we’re losing elections because we’re not hard-ass enough on immigration? [scattered applause] Well, I don’t agree with you. I believe we are losing the Hispanic vote because they think we don’t like them.

I believe that it’s not about turning out evangelical Christians, it’s about repairing the damage done by incredibly hateful rhetoric driving a wall between us and the fastest-growing demographic in America, who should be Republicans.

I believe Donald Trump is destroying the Republican Party’s chances. […]

You think you can win an election with that kind of garbage [self-deportation]? Undercut everything you’ve worked for. So if you think it’s about turning out more people and staying on this path, then you’re setting this party up for oblivion. It’s not about turning out more people, it’s about getting more people involved in our cause.

While Graham’s position that laxer immigration laws is a top priority for American Hispanics isn’t necessarily correct, his points about extreme rhetoric and marginalizing minorities harming Republicans certainly is, especially among Jewish Americans, 84 percent of whom say seeking equal justice is extremely important to them. If the GOP at large heeded Graham’s call on tone and backed off on the “Christian nation” shtick, it might actually have a chance with Jewish voters.